- Home

- Jessi Kirby

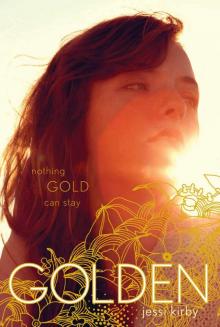

Golden

Golden Read online

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Acknowledgments

About Jessi Kirby

For my grandma, MARIETTA, who introduced me to the simple beauty of Frost’s words, and my grandpa, GERARD, who always believed in mine

life is made of moments. and choices. Not all of them matter, or have any lasting impact. Skipping class in favor of a taste of freedom, picking a prom dress because of the way it transforms you into a princess in the mirror. Even the nights you steal away from an open window, tiptoe silent to the end of the driveway, where darkened headlights and the pull of something unknown beckon. These are all small choices, really. Insignificant as soon as they’re made. Innocent.

But then.

Then there’s a different kind of moment. One when things are irrevocably changed by a choice we make. A moment we will play endlessly in our minds on lonely nights and empty days. One we’ll search repeatedly for some indication that what we chose was right, some small sign that tells us the truth isn’t nearly as awful as it feels. Or as awful as anyone would think if they knew.

So we explain it to ourselves, justify it enough to sleep. And then we bury it deep, so deep we can almost pretend it never happened. But as much as we wish it were different, the truth is, our worlds are sometimes balanced on choices we make and the secrets we keep.

1.

“To a Thinker”

—1936

There’s no such thing as a secret in this town. But I’m keeping this one, just for today. I fold the letter once, twice, three times and slide it into my back pocket like a golden ticket, because that’s what it is. A ticket out. Being chosen as a finalist for the Cruz-Farnetti Scholarship is my version of winning the lottery. It means Stanford pre-med and everything else I’ve worked for.

Icy wind sears my cheeks red as I cross the school parking lot, and I curse Johnny Mountain for being right when he forecast the late spring storm. If the biting wind and swirling white sky are any indication, we may be graduating in the snow, which is not at all how I pictured it. But today I don’t really mind. Today the wind and I burst through the double doors together, and it carries me like someone who’s going places, because now it’s official. I am.

Kat’s already at my locker when I get there and it gives me the smallest pause. We don’t keep secrets from each other. Her eyes run over me, top to bottom, and she smiles slowly. “You look like you’re in a good mood.” It’s more friendly accusation than casual greeting, and she punctuates it by leaning back against the blue metal of the lockers and waiting expectantly.

“What? I can’t be in a good mood?” I reach around her and spin the lock without looking at the numbers, try to hide my smile.

She shrugs and steps aside. “I’m not. This weather sucks. Mountain says it’s gonna be the worst storm in ten years or some bullshit like that. I’m so over the frickin’ snow. It’s May. We should be wearing tiny shorts and tank tops instead of . . . this.” She looks down at her outfit in disdain.

“Well,” I say, trying to pull my mind away from visions of the red-tiled roofs and snowless breezeways of Stanford, “you look cute anyway.”

Kat rolls her eyes, but straightens up her shoulders the slightest bit and I know that’s exactly what she wanted to hear. She stands there looking effortless in her skinny jeans, tall boots, and a top that falls perfectly off one shoulder, revealing a lacy black bra strap. Really, cute isn’t the right word for her. The last time she was cute was probably elementary school. By the time we hit seventh grade, she was hot and all its variations, for a couple more reasons than just her tumbling auburn hair. That was the year Trevor Collins nicknamed the two of us “fire and ice,” and it stuck. In the beginning I thought the whole “ice” thing had something to do with my last name (Frost), or maybe my eyes (blue), but over the years, it’s become increasingly clear that’s not what he meant. At all.

Kat shuts my locker with a flick of her wrist as soon as I unlock it. “So. There’s a sub for Peters today, a cute one I’d normally stick around for, but I’m starving and Lane’s working at Kismet. Let’s get outta here and eat. He’ll give us free drinks and I’ll have you back by second period. Promise.” She’s about to come up with another inarguable reason for me to ditch with her when Trevor Collins strolls up. Even after this long, that’s still how I think of him. Trevor Collins. It was how he introduced himself when he walked into Lakes High in seventh grade with a winning smile, natural charm, and the confidence to match.

His eyes flick to me, not Kat, and heat blooms in my cheeks. “Hey, Frost. You look saucy today. Feelin’ adventurous?” He dangles a lanyard in front of me, and a smile hovers at the corners of his mouth. “I got the keys to the art supply closet, and I could have you back before first period even starts. Promise.” He hits me with a smile that lets me know he’s joking, but I wonder for a second what would happen if I actually said yes one of these days.

I meet his eyes, barely, before opening my locker so the door creates a little wall between us, then give my best imitation of disinterested sarcasm. “Tempting.” But between his dyed black hair and crystal blue eyes, it kind of is. I have no doubt a trip to the art supply closet with him would be an experience. Half the female population at Lakes High would probably attest to it, which is exactly why it’ll never happen. I like to think of it as principle. And standards. Besides, this has been our routine since we were freshmen, and I like it this way, with possibility still dancing between us. From what I’ve seen, it’s almost always better than reality.

Kat blows him a kiss meant to send him on his way. “She can’t. We’re going to get coffee. And she’s too good for you. And you have a girlfriend, jackass.” There’s that, too, I remind myself. But I’ve never really counted Trevor’s girlfriends as legitimate, seeing as they don’t generally last beyond being given the title.

“Actually, I’m not,” I say a little too abruptly. “Going to get coffee, I mean.” I shut my locker and Trevor raises an eyebrow, jingling his keys. “I uh . . . I can’t skip Kinney’s today. He’s got some big project for me.” Oh, the lameness.

Kat rolls her eyes emphatically. “You don’t actually have to show up to class when you’re the TA and it’s last quarter. You do realize that, right?”

“You don’t have to,” I say, matching her smart-ass tone, “because Chang has no idea she even has a TA. Kinney actually realizes I’m supposed to be there.”

The bell rings and Trevor takes a step backward, holding up the keys again. “Best four minutes you ever had, Frost. Going once, twice . . .”

I wave him off with a grin, then turn back to Kat, who’s now giving me her you know you want to look. “Never,” I say. I know what’s coming next, and I’m hoping that’s enough to squash it.

But it’s not, because as we walk, she bumps my hip with hers. “C’mon, P. You know you want to. He’s wanted to since foreve

r.”

“Only because I haven’t.”

“Maybe,” she shrugs. “But still. School’s gonna end, you’re gonna wish that just once, you’d done something I would do.”

I stop at Mr. Kinney’s doorway. Now it’s me with the smile. “You mean did, right? Because I distinctly remember my best friend being the first girl here to kiss Trevor Collins.”

“That was in seventh grade. That doesn’t even count.” A slow smile spreads over her lips. “Although for a seventh grader, he was a pretty good kisser.”

I just look at her.

“Fine,” Kat says in her dramatic Kat way that communicates her ongoing disappointment every time I plant my feet firmly on the straight and narrow road. “Go to class. Spend the last few weeks of your senior year pining over the guy you could have in a second while you’re at it. I’ll see you later.” She smacks me on the butt as she leaves, right where my letter is, and for a second I feel guilty about not telling her because this letter means that Stanford has gone from far-off possibility to probable reality. But leaving Kat is also a reality at this point, and I don’t think either one of us is ready to think about that yet.

When I step through Kinney’s door, future all folded up in my back pocket, he’s headed straight for me with an ancient-looking box. “Parker! Good. I’m glad you’re here. Take these.” He practically throws the box into my arms. “Senior class journals, like I told you about. It’s time to send them out.” His eyes twinkle the tiniest bit when he says it, and that’s the reason kids love him. He keeps his promises.

I nod, because that’s all I have time to do before he goes on. Kinney drinks a lot of coffee. “I want you to go through them like we talked about. Double-check the addresses against the directory, which’ll probably take you all week, then get whatever extra postage they need so I can send them out by the end of the month, okay?” He’s a little out of breath by the time he finishes, but that’s how he always is, because he’s high-strung in the best kind of way. The million miles a minute, jump up on the table in the middle of teaching to make a point kind of way.

Before I can ask any questions, he’s stepped past me to hold the door open for the sleepy freshmen filing in. Most of them look less than excited for first period, but Mr. Kinney stands there with his wide smile, looks each one of them in the eye, and says “Good morning,” and even the grouchy-looking boys with their hoods pulled up say it back.

“Mr. Kinney?” I lug the box of journals a few steps so I’m out of their way. “Would you mind if I take these to the library to work on them?”

“Not at all.” He winks and ushers me on my way with the swoop of an arm. “See you at the end of the period.” Right on cue, the final bell rings and he swings his classroom door shut without another word.

I linger a moment in the emptied hallway and peek through the skinny window in his door as students get out their notebooks to answer the daily writing prompt they’ve become accustomed to by this point in the year. Sometimes it’s a question, sometimes a quote or artwork he throws out there for them to explain. Today it’s a poem, one I’m deeply familiar with, since my dad has always claimed we’re somehow, possibly, long-lost, distant relatives of the poet himself.

I read the eight lines slowly, even though I know them by heart. Today though, they hang differently in my mind—too heavily. Maybe it’s the unwelcome, swirling wind outside, or the fact that so much in my life is about to change, but as I read them, I feel like I have to remind myself that just because someone wrote them doesn’t make them true. I would never want to believe they were true. Because according to Robert Frost, “nothing gold can stay.”

2.

“A breeze discovered my open book

And began to flutter the leaves to look”

—“A CLOUD SHADOW,” 1942

The tape sealing the box of journals snaps like a firecracker when I jab my pen into it. Ms. Moore, the librarian, looks up from her computer momentarily then goes back to scanning in books in a quick rhythm of beeps just like at the grocery store. I’ve come here plenty of times before to do projects for Mr. Kinney, so she doesn’t question me. I settle in, happy with the small measure of freedom, but when I look down at the open box packed tight with sealed manila envelopes and realize what a pain it’s going to be to track down every single address, I half wish I would’ve taken Kat up on her offer to ditch.

The other half of me wishes I had Mr. Kinney for English this year and not just my TA period. So I could be a part of this. Every year he makes a big show of gifting each of his seniors one of those black-and-white marbled composition books after spring break. Their only assignment for the remainder of the school year is to write in it. Fill it up with words that make a picture of who they are, things they may forget later on, after so many years, and want to look back on. Sort of a letter to their future selves. I know this because Kat did get Kinney, and the day she got her journal she started writing in it like crazy, which is funny since she doesn’t usually care about assignments she’s going to get a grade on, let alone work that won’t count for anything.

But that’s where Mr. Kinney’s a genius. He realizes that all of us are a little self-absorbed. It’s human nature. And so when his students get a chance to preserve what they see as important and worthy about themselves, they do. Then on graduation day, they hand over their journals, all sealed up with hope and pride and secrecy. And ten Junes later, those same kids who are now legitimate grownups get a brief little chapter of their teenage lives in the mail.

I know if I asked he’d give me a journal and let me slip it in with the others so that in a decade I could read the words of my seventeen-year-old self. More than once I’ve thought about it. But every time I do I come back to the same thought—what if ten years from now I got a chance to read about who I’d been, and I regretted it. What if I read it and saw past the accomplishments, straight through to all the things I missed while I was busy chasing them. I might wish I had done things differently.

The envelopes in the box are lined up neatly and sealed with a clear strip of undisturbed tape across each flap. Mr. Kinney’s done this project for so long that even if he did get curious and peek in the beginning, the musings of high school seniors probably didn’t hold his attention for very long.

I grab my first stack, bring them over to the computer station and put in Kinney’s password. Once I’m in the alumni directory, the first few go quickly since they’re in alphabetical order and they’re post office boxes that haven’t changed, according to the computer. It’s not all that surprising, since a lot of people don’t ever really leave town. I vaguely recognize one or two of the names, but wouldn’t be able to put a face to them. It’s small here, but not small enough that you actually know everyone. On the other hand it can feel like everyone you run into somehow knows you. Or your mom, in my case.

I roll through the first few names, and pretty soon I’ve got a rhythm and a system, and I can check addresses and daydream at the same time. Only now Stanford may not qualify as a daydream. It feels infinitely more real since yesterday, when I found the thin envelope from the Cruz Foundation in my mailbox. Much different from the early acceptance letter that came months ago. The excitement and relief that letter brought were all tempered with the knowledge that there are hundreds of thousands of dollars between getting in and actually being able to go. It was why I’d spent every waking moment of my life since then searching for ways to make it happen.

And now I have one in my back pocket. So today, instead of running numbers through my head, or wondering if I should’ve revised the application essays one more time, I let myself replay the morning exchange with Trevor. And I revise that instead. In this new version, when he dangles the keys in front of me, I’m the one who raises an eyebrow, right before I take them from his hand and lead him, dumbfounded, to the art closet.

I’ve never actually been in there, but in my mind’s eye, it’s dimly lit, with tubes of paint and coffee cans full of bru

shes lining the shelves—things that might go clattering to the floor if I were brave enough to ever meet his eyes longer than a second. And since it’s my daydream, I am, and I do. Trevor smiles in slow motion as he tilts his chin down to kiss me after six years’ worth of missed chances, and then—

The name on the next envelope snaps me back like a rubber band. I stare. Breathe. Stare some more.

Julianna Farnetti.

I look around, chilled. That can’t be right. But it’s right there in front of me, written in black ink with big loopy pen strokes just as gorgeous as she was. My first impulse is to see if anyone else saw. The clock ticks away the seconds on the wall. In one row of stacks are a couple of younger girls whispering and trying to look like they’re looking for books to check out. Ms. Moore’s keeping tabs on them from behind her computer, and the library TA, a tragically nerdy boy named Jake, shoves a book back onto the shelf then straightens out the ones around it for the millionth time. None of them look at me, but I’m nervous all of a sudden because right now it feels like I’m holding in my hands something I shouldn’t be. Like I’ve just brushed my fingers over a ghost. And by all accounts and definitions, I have.

Every town has its stories. Stories that have been told so many times by so many different people they’ve worked themselves into the collective consciousness as truth. Julianna Farnetti is one of Summit Lakes’. Shane Cruz is the other. And theirs—it’s a story of perfection lost on an icy road. They were one of those golden couples, the kind everyone adores and envies at the same time. Meant to be together forever. Teenage dream realized.

And both of them are frozen in time on a billboard at the edge of town for everyone to see. From behind a thick layer of plexiglass that’s replaced every few years, they smile their senior portrait smiles like they don’t know people have stopped looking for them. Somewhere along the line, the words on the billboard changed from MISSING to IN LOVING MEMORY OF, and I can remember thinking how sad that was, but it was bound to happen. Their parents buried empty coffins.

The Secret History of Us

The Secret History of Us Moonglass

Moonglass Golden

Golden In Honor

In Honor Things We Know by Heart

Things We Know by Heart The Other Side of Lost

The Other Side of Lost